Exploring Sound Design Tools: Reformer Pro

/Kroto's Audio Reformer Pro is a unique tool for sound design. Here is a look at the software from a practical everyday perspective. I will focus on how it can improve your workflow and also on how it can spice things up on the creative side when doing sound design. I encourage you to grab the demo version and follow along.

Technology

Basically, Reformer takes an input (another recording or a live microphone signal) and uses its frequency and dynamics content to trigger samples from a certain library, creating a new hybrid output.

In other words, it allows you to "perform" audio libraries in real time like a foley artist performs props.

Versions

Reformer uses a freemium pricing model and comes in two flavours, vanilla and pro. The first one is completely free but only allows you to use certain official paid libraries. These can be purchased on the Krotos Audio Store where you'll find a huge selection of different libraries.

The pro version uses a paid subscription model and offers more advanced features. This is the one I'll be covering on this post. This version allows you to load up to four libraries at the same time and do a real time mix between them (the free version only allows to load one library per plugin). More importantly, it also gives you the power to create your own Reformer libraries using your sounds.

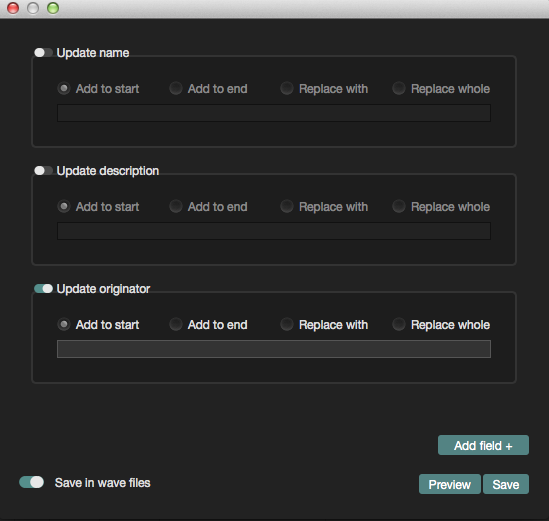

Interface

As you can see on the right hand side, Reformer Pro controls are quite simple and self-explanatory. Nevertheless, here are some features worth mentioning:

Since you can load four libraries at a time, the X/Y Pad on the left hand side of the plugin will allow you to mix and mute them independently.

The Response value (bottom left corner) changes how fast reformer is processing incoming audio. In general, faster responses work better with sudden transients and impacts while slower values will work better with longer sounds. If you notice undesired clicks or pops, this is the first thing you should try to tweak.

The Playback Speed functions as a sort of pitch control allowing you change the character and size of the resulting signal.

Reformer Workflows

As you can see, Reformer offers an imaginative way of manipulating sounds but how can this be helpful in the context of everyday sound design and mix work? Here are some ideas:

Sync: To quickly lay down effects in sync with the picture using your voice or some foley props. For example, covering a creature's vocalizations by hand is always very time consuming and on these kind of tasks is probably where Reformer shines the most.

Substitute: Imagine you have all the FX laid down for a certain object or character and now you have to change all of them to a different material or style. In this case, you could keep the original audio, since it has the correct timing and use it to drive a reformer library with the proper sounds.

Layer: Once you've stablished a first layer for a sound, you can use reformer to add more layers that will be perfectly in sync with no effort.

Make the most of a limited set of sounds: Sometimes you find the perfect sound to use for something but you don't have enough iterations to cover everything. You can create a reformer library with these few sounds and, playing with the playback speed, response time and wet/dry controls, get the most of them in terms of different articulations and variations.

Creating your own libraries

Reformer Pro includes an Analysis Tool that allows you to create custom libraries with your own audio content. I won't go into much detail about how to do this since the manual and this video covers the topic perfectly and the whole process is surprisingly fast and easy. I encourage you to try to create your very own library too.

Ideally, you should use several sounds that follow a sonic theme so you can have a cohesive library. At the same time, these sounds need to be varied enough in terms of frequency and volume content so you can cover as many articulations as possible.

From a technical standpoint, make sure your files are high resolution, clean, closed mic'd and normalized.

As an example, I created ghostly, sci-fi monster voice library using sounds I created with Paulstretch (see my tutorial for Paulstretch here).

You can hear below some of the original samples that I used to build the library. As you can hear, I tried to mix different vocalizations and frequencies:

And here is how the built library behaves and sounds when throwing different stuff at it. The first sounds are the result of monster like vocalizations and you can hear how the library responds with different combinations of timbres. The last sound on the clip is interesting because is the result of the library responding to a ratchet or clicking sound. As you can see is always worth trying to throw weird stuff at reformer to see how it responds.

You can find this library ready to use for reformer in the link below and give it a go:

Ghostly Monster Reformer Library.

Reformer as a creative tool for sound design

In my view, Reformer is not specifically designed for creative sound design as it lacks depth in terms of how well you can manipulate and control the final results. I miss having some control on how the algorithm creates the output signal in a similar way Zynpatiq's Morph plugin has it. But again, I understand sonic exploration is not the main aim of Reformer. Having said that, you can still achieve interesting designs mixing together elements from different kinds of sounds.

For example, we can use a recording with some interesting transients, like a rattling noise to drive some different libraries. Here is the result with a bell:

As you can hear, Reformer takes the volume information and applies it to the bell timbre. And here is a hum and the same rattle creating some sort of fluttering engine or mechanical insect sound. Just for fun, I also added a doppler effect to add movement:

Being able to control any sound with your own source of transients opens a huge window of possibilities. For example, you could use a bicycle wheel as an instrument to perform different movements and articulations. Pretty cool.

I'm just scratching the surface here. There are many more creative ideas that I would want to try. The demo version only runs for 10 days so make sure you can really go for it during those days.

Conclusions

Reformer is a very innovative tool that for sure makes you think in a different way about sound design. Being able to sync and swap sounds on the fly is probably where Reformer shines the most, allowing you to perform recorded libraries live as a foley artist would do. Definitely worth a try.